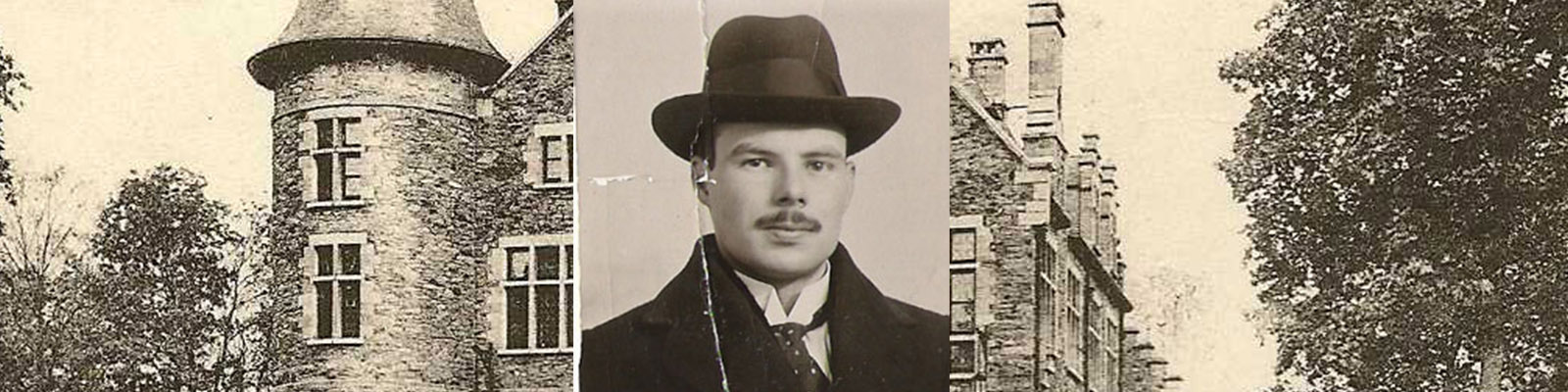

L. O. Smith’s Grandson – The Prince who saved tens of thousands of lives

The Swedish-Romanian prince Constantin Karadja lived a dramatic life. He was the grandson of the brännvin king L. O. Smith and grew up in a cosmopolitan environment. Under the threat of Nazism, he became a human rights advocate and succeeded in saving the lives of tens of thousands of people, mainly Romanian Jews.

For many, Constantin Karadja is an unfamiliar name. However, his heroic work in the 1930s and 1940 means he has few equals in 20th century history. Using diplomacy and his contacts, he quietly managed to save a large number of people from deportation to Nazi concentration and death camps.

Constantin Karadja was born in 1889 in The Hague in the Netherlands. At the time, his father Prince Jean Karadja, who had Greek ancestry, was serving there as the ambassador of the Ottoman Empire. His mother was Mary Smith, the youngest daughter of the brännvin king L. O. Smith, whose wedding had been celebrated in great style in Stockholm in 1887.

Constantin grew up with his sister Princess Despina (born in 1892) in an international atmosphere. It was a matter of course to regard Europe – yes, perhaps even the whole world – as the backdrop to their lives.

A Belgian castle

Prince Jean Karadja could not tolerate the air in The Hague and so for health reasons the family moved elsewhere, first to London, and then in 1893 to Les Concessiones castle in the Belgian resort of Bovigny near the border with Luxembourg. The castle was built in 1880 in the New Renaissance style, but the prince couple, Jean and his wife Mary, still spent large sums of money on rebuilding and renovating it in line with the latest fashion.

But the family were not to experience happiness there for long. Prince Jean Karadja became ill and passed away in August 1894. He was laid to rest in an underground crypt in a newly erected Greek Orthodox chapel next to the castle. The crypt would later play a role in Mary’s interest in spiritualism.

Mary remained at the castle with her children. There they lived in a luxury home, looked after by Swedish servants, among others. But she also spent parts of the year in Stockholm, where she wrote her plays and arranged soirées for ladies. The children also got to experience idyllic Swedish summer holidays in rented homes in the archipelago.

Spiritualism and seances

In the years around the turn of the 20th century, Mary’s time was increasingly filled by her occult interests. She invited mediums from all corners of the world to her Belgian castle, where seven guest rooms were prepared to house clairvoyants and spiritualist friends. Seances were organised and invited guests had the chance to observe strange light phenomena and how heavy objects appeared to levitate. When Mary was in London, she received messages “of a private nature” from her late husband urging her to return to the funeral chapel in Bovigny. There Mary gently opened the squeaky gate and, according to her own statement, met Jean Karadja again.

Her son Constantin, of course, experienced part of this spirit world, but also had other interests. In Stockholm he studied at the Beskowska school and was then sent to England to study law, first at Framlingham College in Suffolk, and later in London, where he graduated. He wanted to be a diplomat, like his father, and went into the service of the Ottoman Empire.

Married his cousin

In 1916, as the First World War raged on, he married his cousin, Princess Marcelle Karadja in Bucharest. Due to the international situation at the time, Mary couldn’t attend the wedding. The young couple decided to settle in Romania, where Constantin was given a position at the Foreign Ministry, where he began his career as a Romanian diplomat.

The Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919 and with it came hope for a new, brighter era. Mary decided to move to Locarno in Switzerland. There she lived in Villa Lux (“Light”) with a lovely view over Lake Maggiore. The villa had nine balconies so Mary was able to follow the sunshine all day. At the same time, Constantin helped sell the childhood home in Belgium to a wood merchant from Bastogne.

Living in Stockholm

Constantin also had close ties to Sweden, where he had spent much of his school years. As a Romanian Foreign Ministry official, he had the chance to see more of Sweden. In April 1928, he moved with his wife to Stockholm after being appointed Consul General at the Romanian legation. Constantin spent much of his time educating a Swedish audience about Romania. He wrote articles and gave talks.

But political unrest once again appeared on the horizon. The fateful year was 1933, when Constantin Karadja arrived in Berlin to serve as Romanian Consul General. That was the year that Adolf Hitler was appointed German Chancellor and the Nazis gained political power in Germany. Karadja was shocked by the persecution of the Jewish population and the open racism aroused his disgust. Behind the scenes, he began working to help Romanian Jews in Germany who were at risk of suffering Nazi reprisals.

Protested against “Kristallnacht”

During the pogrom of 9 November 1938, which the Nazis called “Kristallnacht”, synagogues and business premises owned by Jews were destroyed. Constantin drew up lists of those affected and wrote to his superiors at the Foreign Ministry requesting that Romania protest against the violence and demand that Germany compensate the victims. Constantin also initiated a plan to give Romanian Jews Romanian passports and thus the opportunity to escape to Romania.

In 1941, Constantin was appointed head of the passport authority at the Foreign Ministry in Bucharest. There, he was able to intensify his efforts to take protective measures on behalf of Romanian Jews, both those living in Germany and in the states occupied by the Nazis. But at times he was fighting an uphill battle, as the Romanian government did not consider itself bound to guarantee the protection of Romanian Jews.

Constantin Karadja showed courage as he defied his government’s laissez-faire attitude. He never stopped writing letters and used all his political and diplomatic contacts to enable Jews to return safely to Romania. He impressed on the Romanian government that it could be complicit in Nazi genocide and be held accountable for war crimes after the war.

Died in poverty

The struggle for human rights and human life was Constantin Karadja’s great achievement. However, he himself received no recognition during his lifetime. In 1947, he was dismissed by the new Communist regime and also denied a pension. In 1949 he was given a position as a translator at the Swedish Embassy in Bucharest, but his salary was low. Prince Karadja died in poverty the following year, in 1950, with an arrest warrant from the Romanian secret police Securitate hanging over him.

Only much later did Constantin Karadja get the attention he deserved. In 2005, he was give the Israeli award “Righteous among the peoples” by Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. His life was depicted in a biography by Joakim Langer and Pelle Berglund in 2009.