Poor quality spirits and the first vodka war

Having made a fortune on spirit trade, L.O. Smith decided to start producing his own vodka. He had seen the harmful effects of bad liquor in his life and was keen to improve the general quality of the produce. He read everything that had been published on the subject, and came to the conclusion that the biggest culprit was the substance known as fusel alcohol. During a trip to France and Paris, he heard about Savalle, a company that had found a way to remove impurities from alcohol.

To find out how dangerous fusel alcohol was, Smith carried out experiments both on animals and on humans. The results convinced him of the harmful effects, and he decided to compete with the Swedish distilleries.

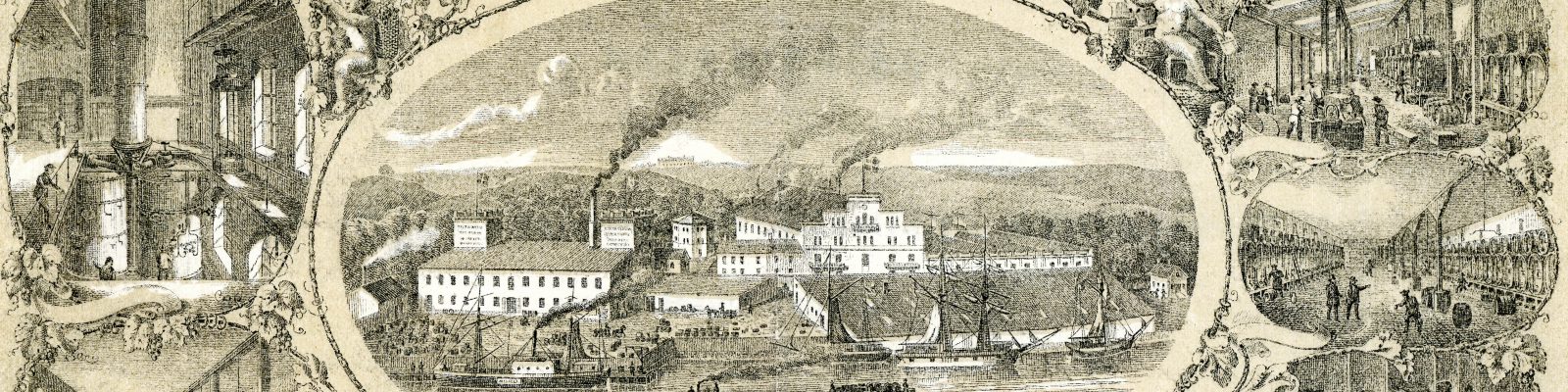

At an auction on April 30, 1868, he bought a bankrupt kerosene factory on the island of Reimersholme in Stockholm. Soon enough, the factory was filled with 1,000 sheet metal containers and 24 carbon filters. The existing distillation equipment, which had been constructed to contain 11,000 liters of kerosene, was rebuilt as a purifier.

When everything was in place, Smith started a campaign that aimed to crush his competitors. In meetings with politicians, he argued that the current legislation should be revised. He tried to persuade them to phase out the public liquor stores and suggested withdrawing the municipal tax on spirit sales. Smith thought that it was wrong that local municipalities could make a profit on people’s drinking habits.

In 1871, the Swedish parliament decided that individual cities no longer should have the right to give the public liquor stores full control of the spirit trade, and the manufacturing legislation was softened. This was good news for Smith. However, in the autumn of 1876, the city council in Stockholm was offered the exclusive right to sell alcohol over the next five years in the city.

Smith and his company Win- & Sprituosa AB offered the city half a million SEK in annual tax for the right to sell spirits. For some reason, his offer was declined. Instead, the license was given to Stockholms Utskänknings AB. Smith was also rejected as a supplier of spirits, which made Stockholms Utskänknings AB a monopoly. The situation led to financial problems for Smith, and when Stockholms Utskänknings AB refused to do business with him, he was prepared to declare war.

On September 12, 1877, Smith opened his own shop at the factory on the Stockholm island of Reimersholme. He could do this because the island belonged to the municipality of Brännkyrka and not the municipality of Stockholm. To make sure that people would be able to visit his shop, Smith set up a boat service between the island and different parts of the city. The service ran every 20 minutes and was hugely successful. According to Smith himself, the store had up to 25,000 visitors a day. Smith also organized wine auctions on the island. In total, more than one million wine bottles were sold at Reimersholme. Of course, this meant that the sales in Stockholm city dropped drastically. Still, Smith had financial problems.

In order to end the competition once and for all, he began to investigate the effects of poor quality spirits once again. In 1878, he arranged and paid for an alcohol congress in Paris, inviting scientists from all over the world. Even the overheads for the Swedish representatives were paid by Smith. At the end of the congress, it was decided that all ”governments should be encouraged to take every measure to ensure that spirits are purified as much as possible”. Meeting minutes in hand, Smith visited the Swedish parliament, asking the politicians to act accordingly. Unfortunately, there was not much interest on the issue. The proposal was rejected and the war continued.

The vodka war finally came to an end in 1880, when other owners in Smith’s company attempted to have him removed from the company. While Smith was abroad for health reasons, the coup-makers saw an opportunity to dissolve the company. They followed the rules and announced an extra general meeting in the press. The idea was to sell the company to the coup-makers for a low sum, and they would then start a new company.

Smith heard rumors about the plans and returned to Stockholm in disguise. When the extra general meeting began, Smith’s horse and cart appeared outside. Smith burst in and started shouting at the coup-makers. At the end of the meeting, Smith had sold his shares for 1,200,000 SEK.

The first liquor war was over and a new company took over the business. Smith left for Venice, where he continued his disrupted vacation. Everything had gone according to plan: He had got rid of the Reymersholme factory and had enough money in his pocket to start the world’s largest liquor factory.