L. O. Smith the father – a stormy story

Charlie, Otto, Lucie and Mary – the names of L. O. Smith’s four children. They grew up to become strong, independent individuals with creative and cultural interests. For a long time their relationship with their famous father was strained and ultimately ended in great turbulence.

As a busy businessman L. O. Smith was far from the ideal father – at least according to current standards. He was often away travelling and devoted the majority of his day to expanding his industrial activities. The daily care and upbringing of his children was left to servants. But in the mid-19th century, this was not an unusual situation in wealthy families. L. O. Smith was thus a typical father of the time. He laid down the basic plan for the upbringing of his children and ensured that they received the best possible education, including at a private school in Geneva. And he had high expectations, especially for his sons.

All you can say about my son the engineer is what he doesn’t do. What he actually does, I have never been able to work out.

His eldest son Charlie (Carl Gustaf) Smith (1862-1927) first attended school in Stockholm and Strängnäs, before continuing his engineering studies at the Polytechnikum (the Federal Polytechnic School) in Zurich. He was not academically gifted, but had a practical inclination and was sent by his father on a study trip to the United States. As a travelling companion and guide L. O. Smith hired the young engineer Axel Tengvall from Sundsvall, who in a letter wrote about his impressions of the family. He described L. O. Smith as “one of the most interesting acquaintances you can make”, but also as an autocrat who “understands how to impose his will”. His wife, however, was “a very kind and charming woman, simple and unaffected, but possibly with too great a soft spot for her children”.

Spoiled children

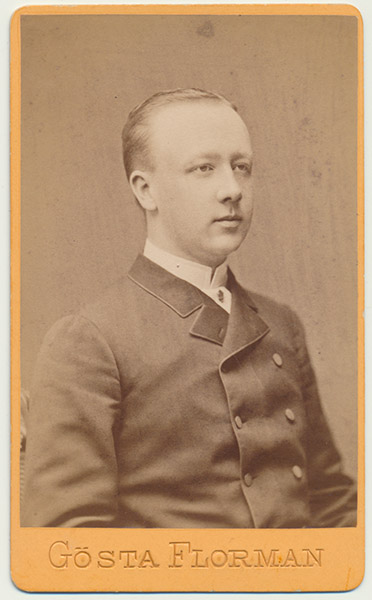

The children seemed spoiled, according to Tengvall. Charlie “looks more prosperous than one has the right to be at that age. A round face and thin, short-cut, light hair gives him a particularly jovial and somewhat good-natured look.” Daughter Mary (Marie Louise) was “a little ninny, who paints watercolours, speaks English and French and intends to learn Italian in the winter.”

Charlie Smith eventually became an engineer and mainly devoted himself to the quarrying industry. He was inventive and filed a number of patents, including for new rock drilling machines, for the development of new methods for the construction of railways and tramways, and for the processing of large stone blocks into paving stones. He was also the father of nine children. But his father L. O. Smith was not impressed. According to great-granddaughter Loulou Eriksson, on one occasion he said of Charlie: “All you can say about my son the engineer is what he doesn’t do. What he actually does, I have never been able to work out.”

At that time, L. O. had a higher regard for his son Otto Smith (1864-1935), at least initially. Otto was academically gifted and studied economics and political science at the universities of Leipzig and Tübingen. He concluded his studies with a doctoral thesis on social subjects that were close to his father’s heart, the Gothenburg Public House System and the labour group movement in Stockholm. Much later, when father and son were at loggerheads, L. O. would argue that he had bought the doctorate for Otto, but whether there was any truth to the claim is unclear.

Close relationship with his daughters

L. O. Smith had a closer relationship with his daughters. His eldest daughter Lucie (1865-1931) married Baron Henric Lagerbielke, who was predicted a brilliant future. But the marriage was not a happy one due to her husband’s alcohol abuse and poor sense of business. Lucie Lagerbielke pursued her cultural and spiritual interests, especially in psychology and spiritualism, subjects that were in vogue at the time. She wrote articles in theosophical journals, along with several literary works.

Today she is best known for her artistic work. In autumn 2019 an exhibition of her watercolour and oil paintings, featuring motifs of landscapes, still life and animals, opened at Millesgården.

Smith’s youngest child, daughter Mary (1868-1943), appears to have been her parents’ favourite. At the tender age of 19 she married Prince Jean Karadja Pasha, the Turkish ambassador to Stockholm, who was almost 30 years her senior. Mary was given the title of princess, but the marriage was short-lived. The Prince died in 1894. Mary Karadja, like her sister Lucie, came to cultivate an interest in spiritualism, and wrote both fiction and drama.

The sudden turning point

L. O. and his children had long enjoyed a good relationship. The evidence for this is the extensive wedding festivities that he arranged for his daughters. In September 1884, L. O. arranged a dazzling wedding ball at his apartment on Blasieholmen for his daughter Lucie and son-in-law Henric Lagerbielke, and when his daughter Mary married her Turkish prince, L. O. had a magnificent wedding pavilion erected at Carlshäll and a large three-storey wooden villa built for the newlyweds at Stilleryd.

But the turning point came in 1890. L. O. Smith was tormented by kidney stones and feared that he would not survive an operation. He therefore gifted large portions of his wealth and several properties to his family. L. O. survived the procedure and seems to have regretted his generous gifts. Perhaps he re-evaluated his entire view of life after hovering on the brink of death.

Break with his first wife

There had been rumours that L. O. had being having affairs, and in 1891 L. O. was sued by his wife, who applied for a division of their estate. It also led to a break between L. O. and his sons, who took their mother’s side. After 1891 he would never see his wife or sons again. His daughters, however, were initially on their father’s side.

L.O. spent time with his daughter Mary, who after the death of Prince Karadja accompanied her father on his travels around the world. She also moved in with him at his Ekenäs villa in Ronneby with her two children and housemaid Anna Viktoria. But that only led to new problems. L. O. Smith became fond of Anna Viktoria and they were married in 1899. That came as a shock to Mary, who after his marriage never spoke to her father again.

A defamation trial

The conflicts within the family lasted for years and followed L. O. Smith all the way to his death bed. His son Otto ensured that financial maintenance was paid from 1905, something which temporarily softened the relationship, but once the money was eventually gone, their relationship became chilly once again. The tone became increasingly bitter and L. O. began spreading various rumours. He was also working on his memoirs that would reveal how his family had betrayed him, and he demanded financial compensation to refrain from publishing them.

Dr Otto Smith to sue his father. Intends to protect the family’s honour against his libellous allegations.

Their eventual publication in autumn 1913 brought the family feud to a head when Otto Smith decided to sue his father for defamation and libel. The news got big headlines. Svenska Dagbladet reported on 23 October 1913 “Dr Otto Smith to sue his father. Intends to protect the family’s honour against his libellous allegations.”

In the following weeks, the press covered in detail the serious accusations that L. O. Smith levelled at his children, including the claim that financial bribery was behind Otto’s doctorate. On 8 December 1913, the municipal court in Karlshamn examined a legal petition of over 140 pages submitted by Otto. The case was then adjourned for seven weeks. But there would never be any further proceedings. The day after, on 9 December, the feud was definitively over when L. O. Smith passed away in his humble apartment in Karlskrona after many tumultuous years and without ever reconciling with his family.