Smith loses “the vodka war” with Spain

L.O. Smith had high ambitions, and he was by no means satisfied by his success in Sweden. In the early 1880s, he set his sights on the international liquor export market. He had learnt that Germany exported quality spirits to Spain and saw a chance to compete. As the export would benefit Sweden’s economy, he contacted a Swedish diplomat in Spain who helped him to set up his new business.

As soon as he got the green light, he started building a huge distillery in Karlshamn. In August 1884, 80 giant cisterns had been put in place. The rectified spirit (the base alcohol) was bought from Russia. The distillery became an important industry in Karlshamn, and Smith doubled the factory workers’ wages.

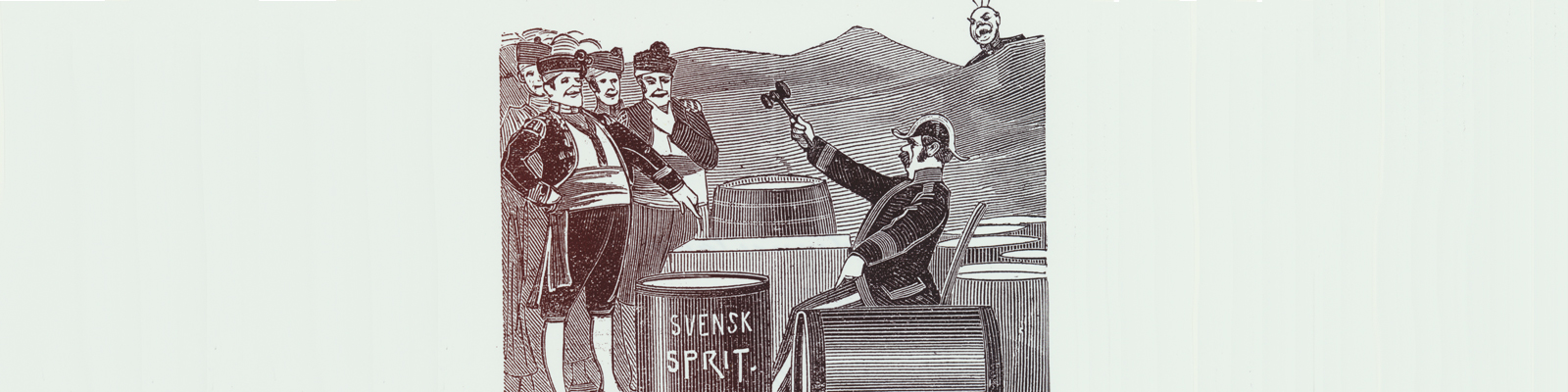

In December 1884, the necessary paperwork was in place. 589 barrels of rectified spirit arrived from Russia on the ship Helix. Business was going well. In January 1885, Smith opened branches in several Spanish cities, including Tarragona, Barcelona and Valencia. The Swedish consul in each city was appointed director. In recognition of his work, L.O. Smith was knighted. Shortly after that, the factory in Karlshamn was rebuilt. 200 electric lamps were installed, which created headlines all over Sweden. The goal was to produce 100 million liters of purified vodka per year. To meet the need for oak barrels, a barrel factory was set up on the Stilleryd property outside Karlshamn. The factory hired 150 men with a combined capacity to produce 250 barrels per day. Smith and his family moved to the area.

To reduce the risks associated with the business in Spain, Smith set up a cooperation with the banking firm Murrieta & Co. The collaboration led to increased revenue, which continued to fund the rectified spirit in cash and kept the price down.

In 1887, Spain and Sweden discussed if and how they would continue their trade treaty. The Karlshamn factory, which had been rebuilt a third time, almost came to a halt during the negotiations. In June, it was finally decided to extend the trade treaty. Smith celebrated by distributing 25 percent of the profits to the shareholders. When production resumed, he also took the opportunity to expand the factory a fourth time. At the end of the year, a record 17 million liters of spirits had been delivered to Spain, Italy, Estonia and Austria.

Despite the impressive volume, Smith realized that the business was not making enough profit. He set off to Russia with the intention of negotiating better prices for the rectified spirit. At the same time, Spain experienced financial problems. To boost their economy, they found a way to terminate the trade deal with Sweden. Instead of raising the customs tariff, they decided to impose a tax on alcohol. In February 1888, the Swedish-Norwegian diplomat Anton Grip received a letter with information about the new tax.

L.O. Smith had 16,000 barrels in Spanish warehouses at the time, and he hoped that the Swedish state would protect his interests. Unfortunately, Anton Grip in Madrid was not particularly interested in helping Smith, even though Sweden’s foreign minister Ehrensvärd explicitly asked him to do so. Grip had more important issues on his mind, for example the negotiations over the pig iron trade deal between Spain and Norway. Moreover, he did not expect that the proposal would go through so fast. Grip therefore decided to wait and see how Germany reacted to the new tax. Meanwhile, Smith was getting unfavorable attention in Spanish media. Grip believed what he read in the news, and was convinced that Smith planned to take advantage of the situation. Smith was suspected of shipping large amounts of spirits to Spain before the new law came into effect. He would then earn more money for himself when the new tax increased the prices.

Finance Minister Ehrensvärd continued to put pressure on Grip to support Smith. At the same time, it looked like the diplomatic crisis between Sweden and Norway would end in military action. Ehrensvärd was reluctant to dismiss Anton Grip from his post.

Sweden protested against the new Spanish law and wanted it to be legally assessed. Spain ignored Sweden’s requests. Just before the law was due to come into effect, L.O. Smith shipped almost 1,000 barrels of liquor into the country. The Spanish Government saw this as an attempt to evade the new tax and suspected that Smith and the Swedish state were in collusion.

Smith did in fact pay the new tax for the cargo, so in the end the suspicions turned out to be false. Despite that, the Spanish authorities ordered Smith to confirm how much liquor he stored in Spain. If he didn’t comply, the liquor would be confiscated.

Spain refused to settle the dispute in arbitration. At the same time, the support Smith had from the Swedish foreign minister Ehrensvärd was suddenly withdrawn.

The stock in Spain was sold and the company in Karlshamn ran out of money.

Eventually Spain confirmed that they would like to settle in arbitration after all. They demanded the right to choose arbitrator, and the Portuguese Count de Casal Ribeiro was appointed. This was a man who had worked as an envoy in Madrid. He had also been admitted to a mental hospital twice. Sweden and the Karlshamn company lost their first international arbitral tribunal.

L.O. Smith personally lost 12 million SEK in the Spanish vodka war, which corresponds to 685 million in today’s currency.

700 people lost their jobs. It is not entirely clear what happened to Ehrensvärd’s support, nor why Anton Grip was so opposed to Smith.

According to the author Pelle Berglund, who wrote the book The Vodka King, the Norwegian Anton Grip played a major role. He hated L.O. Smith and was determined to destroy him. What did Grip have against Smith? Allegedly the reason was that Smith encouraged a Mr. Richter to accept a ministerial post in Stockholm. Richter was unhappy with the job and committed suicide. According to Grip, it was Smith’s fault.

Another theory is that Grip decided not to help Sweden and Smith because it could affect Norway’s negotiations with Spain over pig iron.

Berglund’s theory is that Sweden did stand behind L.O. Smith, but that foreign minister Albert Ehrensvärd stopped putting pressure on Grip to save his own skin. Ehrensvärd sent several letters to Grip, asking him to follow Swedish orders and challenge the Spaniards. In the final letter, Ehrensvärd wrote:

”If you do not follow official orders this time, you will be dismissed! This is a matter of principle – the fact that it concerns liquor is irrelevant.”

This letter is dated July 1888, but it was never posted.

There is a reason why the letter was not sent: Just as the letter was about to be stamped, Ehrensvärd was invited on a fishing trip with the cabinet secretary Carl Bildt and Smith’s old adversary named Smitt. Bildt wanted to avoid a potential diplomatic crisis with Norway, and Smitt was keen to get Smith out of the way. Together, the two of them blackmailed Ehrensvärd. If he sent the letter to Grip, they would reveal that Ehrensvärd had an affair with a ”secret Madame”. Ehrensvärd kept silent and both Sweden and L.O. Smith lost the Spanish vodka war.

If you do not follow official orders this time, you will be dismissed! It is a matter of principle – the fact that it concerns liquor is irrelevant.

The Karlshamn factory was closed down, and the barrel factory in Stilleryd would soon suffer the same fate. Smith tried to start a business in England, but his application to set up the company was rejected by Sweden’s king Oscar II.

A few years later, in 1903, L.O. Smith was granted the right to get compensation from Spain. Unfortunately the Spanish economy had hit rock bottom, and the former vodka king ended up without money anyway. Smith was also accused of having evaded customs tax. The Swedish negotiations were canceled and eventually the case fell into oblivion.

Thanks!

The editor is grateful for the contribution in this text from: Magnus Lindstrand