Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol Exhibition at Spritmuseum Features MSCHF Art Collective

Visitors to Spritmuseum, Stockholm, will get the opportunity to see the rediscovered Absolut Warhol ‘blue’ painting over the summer with the Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol exhibition extended until 14 September.

Visitors will also be able to view art from several contemporary artists engaging with similar themes, including art from MSCHF, the Brooklyn-based art collective known for its thought-provoking and satirical work.

The Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol exhibition, which opened in October last year, coincides with the rediscovery of the Absolut Warhol ‘blue’ painting, the American artist’s interpretation of an Absolut Vodka bottle, more than 40 years after it was painted. The Andy Warhol Exhibition takes visitors through Warhol’s career from a commercial artist in the 1950s to his pop art era, touching on economics, commerce and commodification.

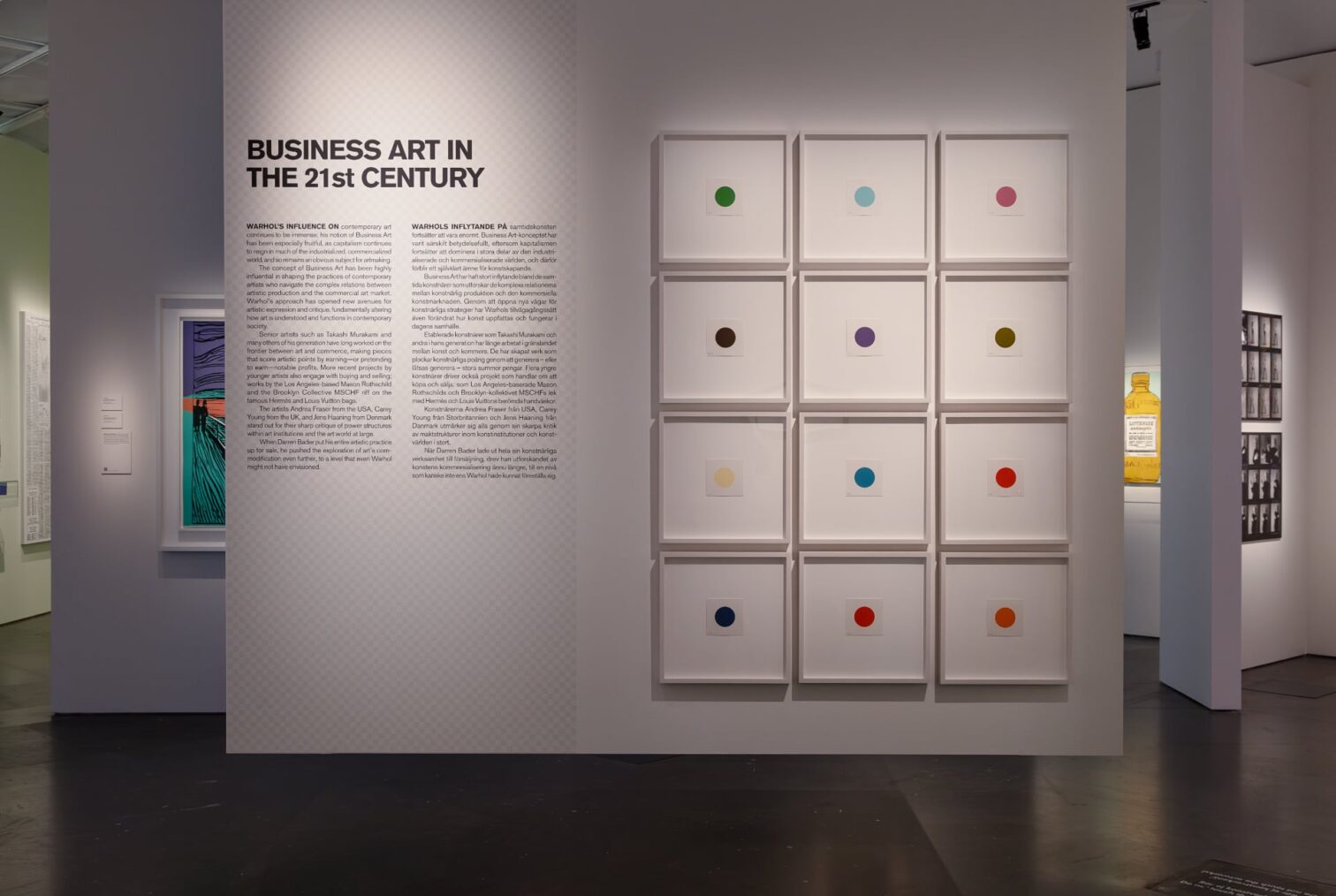

The exhibition displays several works from MSCHF, whose concepts blur the boundaries between art, commerce and technology – and spark debate. And like Absolut, which believes art should be accessible to all, many of its projects open doors for people to own an original piece of work that would typically be out of their reach. These include Possibly Real Copy of ‘Fairies’ by Andy Warhol, which challenges ideas of authenticity and Severed Spots, which questions the nature of value and originality of art – both of which are on show at the Spritmuseum.

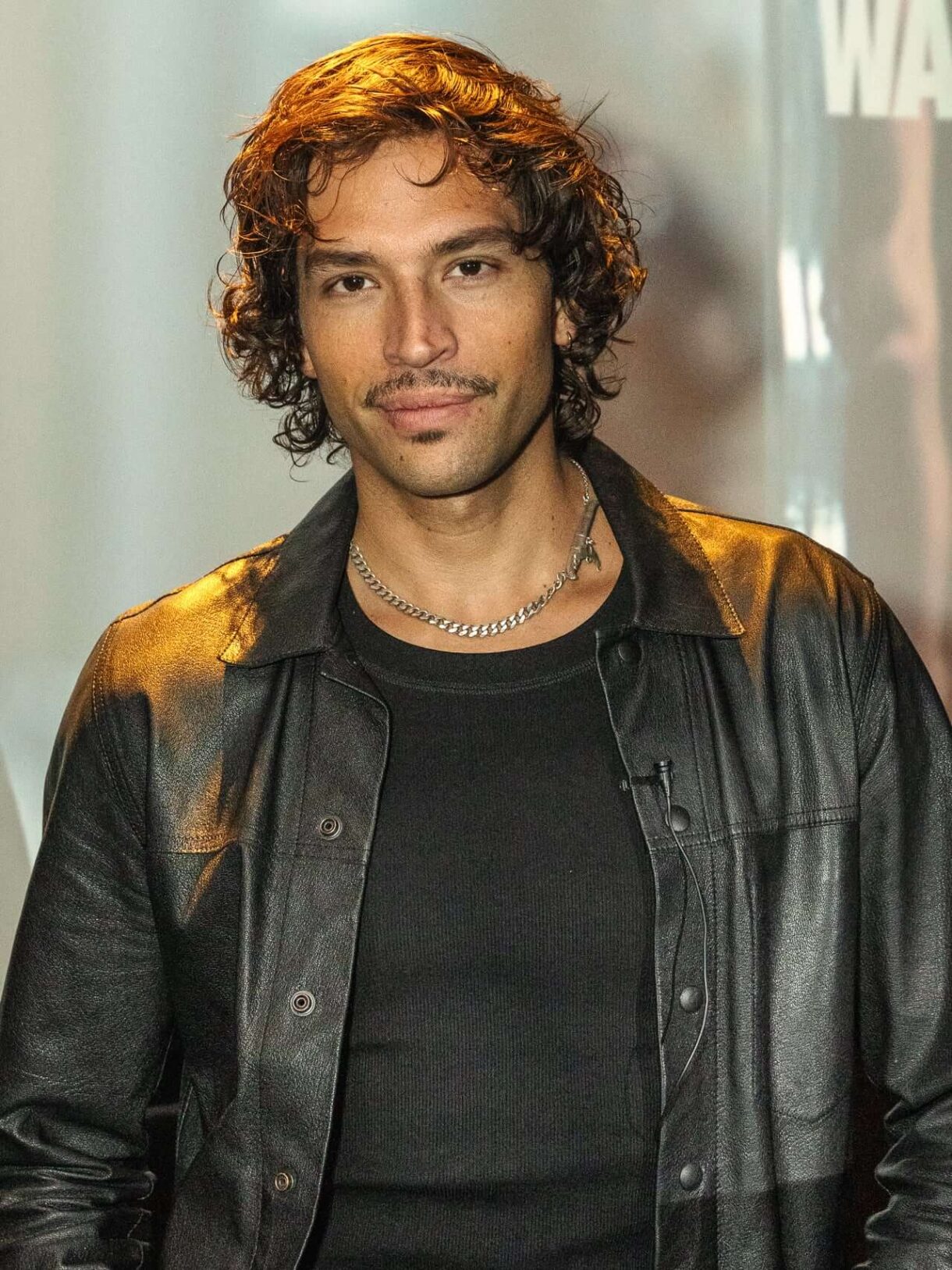

We gathered some of the MSCHF collective together (@Jake Krowicki, @Kevin Wiesner, Hope Harrison and @Lukas Bentel) to find out what MSCHF is and how Andy Warhol has influenced its work.

What is MSCHF?

We are a collective art practice making and creating things, often with a sense of humour, that are physically connected whether it’s shoes, apps, video games or books. There are around two dozen of us who all have different career backgrounds – including art, design, tech, art history and computer science – but having such a range of skill sets enables us to tackle a wide variety of projects.

What has been Warhol’s influence on MSCHF?

Warhol was a trailblazer in operating an art studio as a factory – fully integrating the mechanics and the conveniences of a business model in the production of art. He set the standard for sampling and appropriating people, images and also brands into his work in a way that we do now. He established a set of practices with works like Campbell Soup and these types of companies are the landscape in which MSCHF exists. We’re not going to paint hills; we’re going to paint brand logos! Indeed, we deliberately set up as a company to help us maximise the power behind our work – and being part of this exhibition on business art is the best Warhol context we could ever find ourselves in.

Warhol set the standard for sampling and appropriating people, images and also brands

Can you explain the concept of Possibly Real Copy of ‘Fairies’ by Andy Warhol on show at the exhibition?

It was an experiment in destruction by multiplication. We bought a Warhol drawing from 1954 called Fairies and set up a process to forge the drawing using a robotic arm and a pen, and also the paper in how it had become stained over the years. We made 999 copies and mixed them with the original, in one big pile. We now had 1,000 pieces of original MSCHF artwork. By doing this we had destroyed the drawing’s chain of provenance because now it was extremely difficult to determine which one was the original Warhol. We had wiped out its history and created a situation where anyone claiming to have the original would be highly suspect. The Warhol drawing was more accessible, as each copy cost $250 rather than $20,000 for the original. Today, there are 999 more possible owners of an original Warhol than before! And by selling 1,000 copies, its value multiplied significantly.

What was the idea behind MSCHF’s Damien Hirst-inspired Severed Spots?

We bought one of Damien Hirst’s spot prints for around $30,000, cut out all the spots and then sold each spot individually for $480. When we bought that print, the seller, rather than talk to us about acquiring work by one of the 21st century’s most recognisable artists, spoke to us like a stockbroker by telling us its value would double in five years. We were sitting there thinking, “You have no idea buddy”. We thought we speed the valuation process up a little faster. By the time we had sold all 88 individual spots and the original with the spots removed, we had easily tripled our money. Severed Spots was our way of playing with the market dynamics of the art world.

By the time we had sold all 88 individual spots and the original with the spots removed we had easily tripled our money

Where do your creative ideas come from?

We’d say that the core circadian rhythm of the group is coming up with ideas. Once we come up with an idea, we figure out how to get it done. This can take years or we may sit on the idea for a while. We have thousands of creative thoughts and it becomes a curation process based on feasibility and practicality. Sometimes we want to make money out of a concept, but sometimes we just do it because we love the idea!

One misconception about MSCHF is that people think that we look to get sued [we don’t]

You must be all experts in copyright law, right?

No, but our lawyer, John, is. We quickly realised that most lawyers say “no” because if they don’t and it doesn’t work, there is going to be a problem. One misconception about MSCHF is that people think that we look to get sued, yet every project we’ve done has been something that we believe we could do from a legal perspective.

What has been your favourite MSCHF project so far?

It’s a tricky one to choose but our social experiment called Key4All would be up there. It was a concept that we had played with for a very long time and was related to a well-known video game full of heists and mini-adventures. We got this 2004 Chrysler PT Cruiser and got 5000 sets of keys made, which we then sold for $18 to people in all 50 USA states. People had the opportunity to legally ‘steal’ the car and drive it wherever they wanted, with the understanding that if they left the car, another key holder would be able to come and take it from them.

We dumped the car in Brooklyn and it went from New York to California, running for about nine months before the engine ultimately burned out. The car had a GPS tracker and hotline so people could keep tabs on where it was. In the cycles of people trying to steal it, people trying to liberate it, people breaking it and people repairing it, the project became something in between a play and a reality TV show. Instead of delivering a script, we provided the setting and props.

What’s next for MSCHF?

Creating new work, doing more shows. We come up with ideas all the time and many of them won’t see the light of day. But five minutes ago [MSCHF co-founder Kevin Wiesener, standing at a bar next to an ice bucket] I thought about a big ice cube that you can eat like an apple. How does that sound?