Warhol: where business art meets Absolut art

The rediscovered Absolut Warhol ‘blue’ painting is now back home with the Absolut Art Collection – a compilation of more than 850 works gathered between 1986 and 2004 that cuts across trends, themes and disparate spheres of the art world.

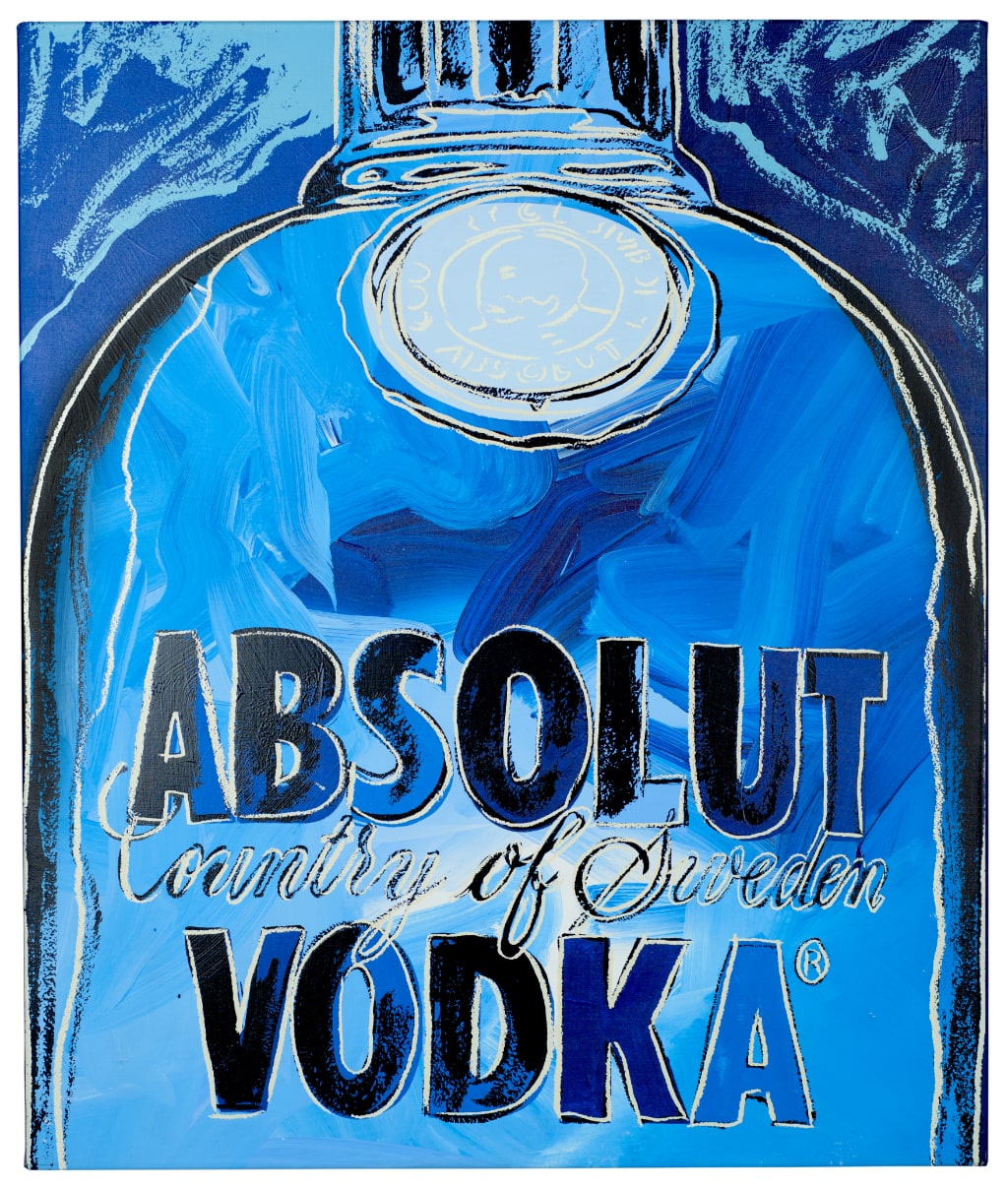

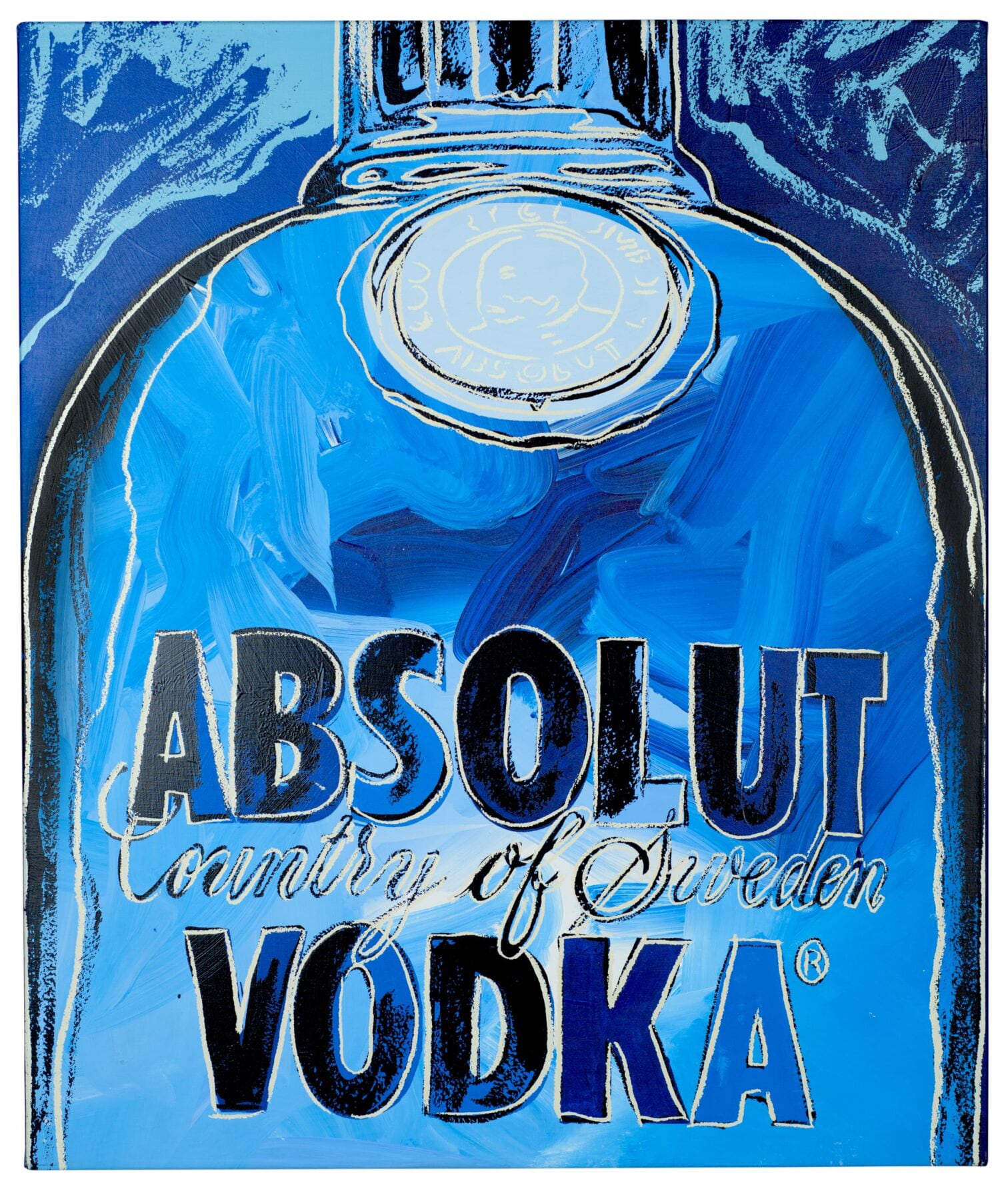

This week, Warhol’s second painting, ‘blue’, is unveiled to the public for the first time at an exhibition in Stockholm – Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol at Spritmuseum.

The exhibition takes visitors through Warhol’s career from a commercial artist in the 1950s to his pop art era, touching on economics, commerce, and commodification. The show also looks at a group of postwar artists and several contemporary artists engaging with similar themes, including Carey Young and the American art collective MSCHF. Working with the exhibition’s curator, the acclaimed Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik, we caught up with the Absolut Art Collection’s very own curator Mia Sundberg to discuss theAbsolut Art Collection and Spritmuseum’s biggest project yet.

Would there have been an Absolut Art Collection without Andy Warhol?

Warhol sparked the Collection and it is because of him that it became such a huge success. He brought in artists such as Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf and this set the level for the collection from the get-go. Warhol made it easy for other artists to accept a “commercial” commission to create a portrait of the Absolut bottle because he had done it first. That was very important. I doubt we would have the Absolut Art Collection had Warhol, or at the very least an artist on his level, not painted the first.

How did the Spritmuseum hear about the rediscovery of Warhol’s Absolut ‘blue’ painting?

For decades there had been rumours of there being two Absolut Warhol paintings. In 2013, I tried to find out more by emailing the late Michael Roux, who was involved in the original Warhol commission. Michael confirmed to me that there were two paintings but only had vague memories of what happened to them. As I wasn’t getting anywhere, I left it, until 2019 when a double-page story appeared in a business section of a Stockholm newspaper about an unknown portrait of the Absolut bottle being up for auction. That is when the telephone started ringing with the media asking us what we knew about it.

I went back to look at an email I had received from Michael, which had ended with a line that had meant nothing to me all those years ago. On rereading the email, he had written, “As I remember, it was in blue tones”. That’s when I realised, oh my, this is the painting! Our museum director immediately went to the museum’s board, which subsequently directed that the painting had to come back [to the Absolut Collection]. We put together a chain of evidence to prove that Absolut commissioned the painting and why it should be returned to the collection. We were asked to present the evidence and as soon as we did, the family who had placed it for auction didn’t hesitate to return it to us.

What was your reaction when you first saw Absolut Warhol’s ‘blue’ painting?

It is a beautiful painting. The interesting thing is how different the two Absolut Warhol paintings are. The original one is so much flatter with more of a silk screen finish. The blue painting is much more expressive; someone has really worked by hand and you can see the marks of the paintbrush. They are very different in that sense.

What is the rationale behind the Money on the Wall exhibition and ‘business art’ theme?

Business art is a term that Warhol himself coined but up until now, has never really been taken seriously. It has just been regarded as one of these ironic statements or jokes that Warhol made. But in 2020, Blake Gopnik published a definitive biography [Warhol: A Life as Art], which, as one of its central themes, focused on exploring the idea of business art. The clichéd way of describing Warhol is that he was at his most iconic in the 1960s before he sold out by selling prints of his iconic images such as Marilyn Monroe and taking commissions from the likes of Absolut. By doing this, he’s considered less complex and less interesting. But Blake in his book and this exhibition looks to turn that around. Warhol is commenting on how commercial our society has become and how art is a part of that by exploring the relationship between art and money.

Warhol is commenting on how commercial our society has become and how art is a part of that by exploring the relationship between art and money.

Is ‘business art’ more than about making money?

Absolutely. It’s much more complex than that. Warhol took all kinds of commissions from companies including making television commercials, for example. As a client, you never knew whether you could use ads made by Warhol or not. Some were so absurd, weird and twisted that companies shut down the contracts and never used them. We have two of these commercials on show including one for a laxative pill. Next to the ad on the wall, there is a framed letter dated 10 September 1965 from Foote, Cone & Belding the agency that commissioned Warhol that reads, “Dear Andy, I’m sorry to say that TV commercials you shot for the new laxative seem to be dead,” and he was paid $25.36 to cover expenses including cost of the 16mm film he used to shoot it.

Do you think that Warhol devalued his art by commercialising it?

This is what Warhol was playing with. If we take the Marilyn image, which was a painting that he first made in 1962 and that became iconic. Five years later he takes the same image and makes a print edition of 250. You are devaluing your own art if you start mass-producing it and selling it very cheaply. You could see that as something he was doing just to make money, or was he rebelling and playing around by provoking? He was so critiqued about becoming too commercial, but he was doing it so deliberately that you have to wonder whether he was trying to expose something about the relationship between art in the world of business.

How did the Spritmuseum’s collaboration with Blake Gopnik come about?

Ever since we received the Absolut Art Collection in 2012, we planned to organise a Warhol exhibition, but we were waiting for the right moment. When we received this [‘blue] painting, it seemed like the perfect time. I started reading up on Warhol and thinking about what perspective we could take. I read Blake’s book and immediately realised that there was material we could use and so I contacted him. Given the history of our two paintings, business and art was the perfect theme for us to explore.

What is your main takeaway from the exhibition?

I was never a Warhol expert and I still am not. Working on the exhibition was the first time I’ve really delved into the work of Warhol and so it was a learning process. The exhibition is inspired by the book, it has the quality of a book. It’s structured as chapters. It starts in the 1950s and it ends pretty much right when he dies. There’s a video in the last section of the exhibition, which is of Andy modelling and it was made five days before he died. Warhol is such a seminal figure in 20th-century art that you can never get around him and you see him in art everywhere. If you asked me if, before the exhibition, he was a favourite artist of mine and would say he wasn’t but I’m much more interested in him now – and even more profoundly aware of how huge his influence was and is. Every time you work closely with an artist and make an exhibition your relationship with that artist changes, they become a little bit like a friend – and it has been no different with this exhibition.